In the central street of Riga, Brīvības iela, there is a bronze statue of a man sitting on a rock and drawing with a pastel pencil. This bearded, oddly-dressed, barefoot man resembles a character from a fairy tale.

However, such an oddball really existed and lived not so long ago. The plaque attached to the rock says: “Artist Irbīte, 1893 – 1944.”

Not like the Rest

You may have noticed that the name on the inscription does not match the one used for the title of the article. Irbe means “partridge”; Irbīte is a gentler form of the same word, “сute little partridge”.

This case is quite unusual. Latvians love diminutives, but to avoid confusion, they rarely apply them to surnames.

Irbe’s entire life can be described as a whimsical sequence of exceptions to rules.

Dull Pupil

Voldemārs Irbe was the seventh child in a poor family. His mother worked as a servant at different farms in Gulbene County. His father worked in the capital for a while, however, earning little and irregularly.

In 1904, the whole family moved to Riga. Voldemārs, who had already turned 11, was enrolled in a relatively cheap parish school.

At first, the boy did well, but as soon as some subjects became difficult for him, he turned lazy. The only subject that still captivated young Voldemārs was God’s Law. He found biblical stories “as exciting as the adventures of Sherlock Holmes”. (1)

After a few unsuccessful years of learning in the parish, the boy started to attend the Drawing and Painting School of the Riga Decorative Painters’ Art Society. He made progress there without any serious troubles. After graduation, Voldemārs Irbe continued his training in the studio of the artist Jūlijs Madernieks.

Enchanted Wanderer

When Voldemārs was 22, an awful thing happened: his father committed suicide. Shocked by the tragedy, Voldemārs turned to the Church for solace and entered the Saint Alexei Orthodox Monastery to work there. He chopped firewood, peeled potatoes, and rung the bells.

World War I erupted, but the young man wasn’t going to fight. Irbe could not understand why he should kill other people and risk his own life.

The monastery was evacuated to the interior of Russia and Irbe followed. He considered becoming a monk so that he would get permission to paint icons.

Saint Peterburg and Moscow impressed the young man. He eagerly visited the best Russian galleries, museums, and churches. The result of his intensive sightseeing was, to put it mildly, unexpected. The monastery’s helper realized that he needed to travel to Egypt.

And, despite wartime and the fact that he had no money, our enchanted wanderer* set out on his journey. During his voyage, Voldemārs paid for food by drawing portraits. Irbe didn’t reach Egypt, yet he managed to reach the Caucasus Mountains.

The Orthodox Monastery of New Athos welcomed him and the lucky artist began working in the icon-painting workshop. Everything was fine… until Voldemārs decided to cross the war zone afresh, this time towards Latvia.

The newcomer’s decision probably hurt the monastery’s priest. He said to Voldemārs:

You are not a human being; you are a bird. A human has to stay on the spot like a stone, but you want to wander” (2).

No one knows how Irbe returned to the capital of Latvia. There, he met his mother, brothers… and a military commission that also wanted to see him.

Self-Proclaimed Idiot

Irbe knew that he could be mistaken for being mentally ill. The artist joyfully declared to the members of the military commission that he was an idiot.

They sent him for treatment to the Nervous and Mental Clinic at Yuryev University. This did not upset Irbe. In the hospital, he enjoyed free food and accommodation, read good books, and drew all day long. The doctors eventually suspected him of cheating; Irbe had to face reality and look for a job.

The artist tried teaching. Unfortunately, he failed all three attempts to maintain a job at school. Irbīte got along with children but refused to dress like a teacher. Voldemārs Irbe always wore dirty, smelly rags and only washed properly once a year, at Christmas time.

Jobless again, he earned a living from his drawings – mainly portraits. Irbe would slip quietly into cafés, sit in a corner, and sketch customers. When the picture was ready, the artist would show it to the depicted person. The portrait usually cost “a little coin” – whatever price which the person was willing to pay.

Many drunk people were rude to the artist who looked like a beggar. In response, he would only apologize.

With regards to alcohol, Irbīte himself did not drink.

Ubiquitous Artist

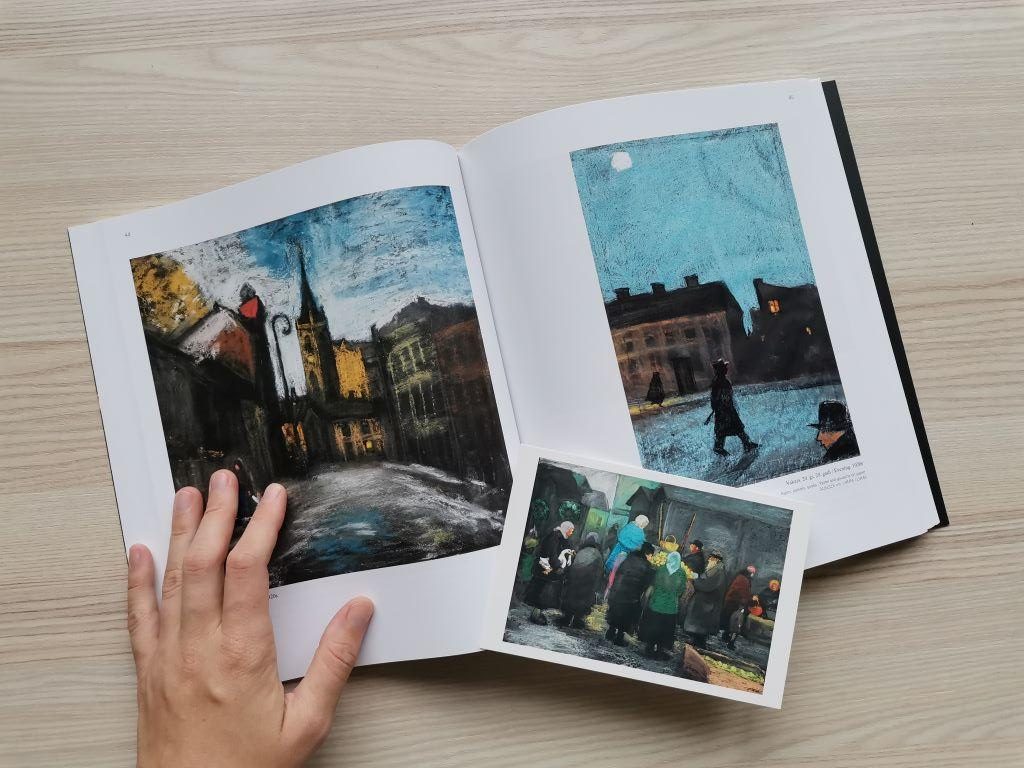

Irbe also liked to draw landscapes and city scenes. He drew in the outskirts and in the city center, in churches and laundries, at public debates and funerals. Residents of Riga considered Irbīte to be a harmless oddball, and his presence embarrassed nobody.

The artist worked very quickly. In his own words, Voldemārs Irbe created a new picture during the time that he could stay standing on one foot. Voldemārs had to assume that pose because he never walked with shoes and his feet were often cold.

Irbīte preferred to work with pastel against a dark background, but if he was short of money, he used any available materials, even wrapping paper.

Many of his pieces were no bigger than the palm of one’s hand. Tiny pictures sold well.

Untrained Enlightener

Irbe felt the need to share his ideas on life but, being poorly educated, expressed his thought incoherently.

Being ill-educated, Irbīte expressed his thoughts incoherently. He felt the need for sharing ideas of life with people, though.

He tried to give a few public lectures (“Why one person causes harm to another”, “On Work” and others). They attracted many listeners. Sadly, the audience perceived Irbe’s speeches as an entertainment show. While he was speaking seriously, the audience was roaring with laughter.

Irbe turned to writing. He wrote almost 30 short books on eternal themes.

These booklets were not meaningless at all. The problem was that Irbe couldn’t keep to a particular subject. As soon as a new concept captured his attention, he readily switched to it: “I also want to say about…” (3)

Of course, no publishing company would print books of that sort for sale. Irbīte printed his discourses at his own expense and offered them to passers-by in the street.

Impoverished Renter of Two Houses

Since Irbe was not affiliated to a creative group of artists, his works rarely appeared at exhibitions. He found an original way to solve this problem. In the summer of 1923, Irbīte held his first solo exhibition in the flat where he lived.

Valda Knāviņa, author of the best biography of Voldemārs Irbe, described that event:

The room was apparently filled to overflowing with pastels, charcoal drawings and watercolors, which were arranged chaotically, pasted onto cardboard, nailed to the wall or leaning against it. In a corner there was a boy humming a song, while other children, encouraged by the artist, were drawing.

Later, the artist borrowed money to rent the whole house (which was, more precisely, a damp, dirty hovel). When it was filled with drawings, Irbīte dared to rent another hovel.

He was too poor to pay for the use of a flat and two houses, and, not surprisingly, had to close his exhibitions before long. Nevertheless, they played their part: some people start talking about the oddball Irbe as a true artist. In 1929, Riga City Art Museum and the State Museum of Art bought more than 50 of his works.

A Victim of a War

1944 was, maybe, the hardest year of the Second World War for Riga. By this time, all city life turned upside down.

Only Voldemārs Irbe lived as if nothing was happening. He drew every day; moreover, the artist was able to rent a humble space for another personal exhibition and exhibited his works again.

One day, when the artist was returning home with paper he had obtained from somewhere, a bomb attack suddenly started. Irbīte perished at the corner of Matīsa iela and Brīvības iela.

The monument to him stands not far from this spot.

The painter Kārlis Neilis, who was a contemporary of Irbe, remarked, (4)

Not only by his manners but also by his appearance, he could be compared with the saints and prophets in medieval painting.

As for me, I would compare Irbīte with Russian so-called “Holy Fools”.

According to Russian Orthodox tradition, it is a terrible sin to kill a Holy Fool. Who was guilty of Irbe’s death? Nobody or everybody?

- Voldemārs Irbe – Valda Knāviņa, Neputns, 2015

- Iz manas dzīves – Voldemārs Irbe, Autora apgādībā, 1928

- Kamdēļ cilvēkam rodas ļaunums no cilvēka? – Autora apgādībā, 1925

- Tie trakie gleznotāju gadi – Kārlis Neilis, Neputns, 2006

- Voldemārs Irbe: atmiņas, atziņas, vērojumi, nostāsti, fakti – sast. G.Pupa, red. Ausma Balcerbule, Preses nams, 1995

- Pārrautā leģenda — nu akmenī un bronzā — atkal dzīva – 20.10.1999., Nr. 345/346, Latvijas Vēstnesis, Aina Rozeniece

*The Enchanted Wanderer is a novel by Russian writer Nikolai Leskov. The main hero of the novel, a young man who was “promised to God”, refused to join a monastery.