Some online newspapers place warnings about shocking content above images that can startle sensitive people.

I should have hidden all the photos from my article under a content warning as well. Once you take a close look at the central scene of the Isenheim Altarpiece, created by a 16th-century German artist, you will remember it forever.

Death without Embellishment

The panel we are talking about today represents the Crucifixion. The subject isn’t unique. Every museum demonstrating treasures of medieval art has dozens of pieces that depict the Savior on the cross. But this artist interprets the biblical motive very boldly.

Instead of showing Jesus Christ in His spiritual grandeur, the painter presents Him beaten and humiliated.

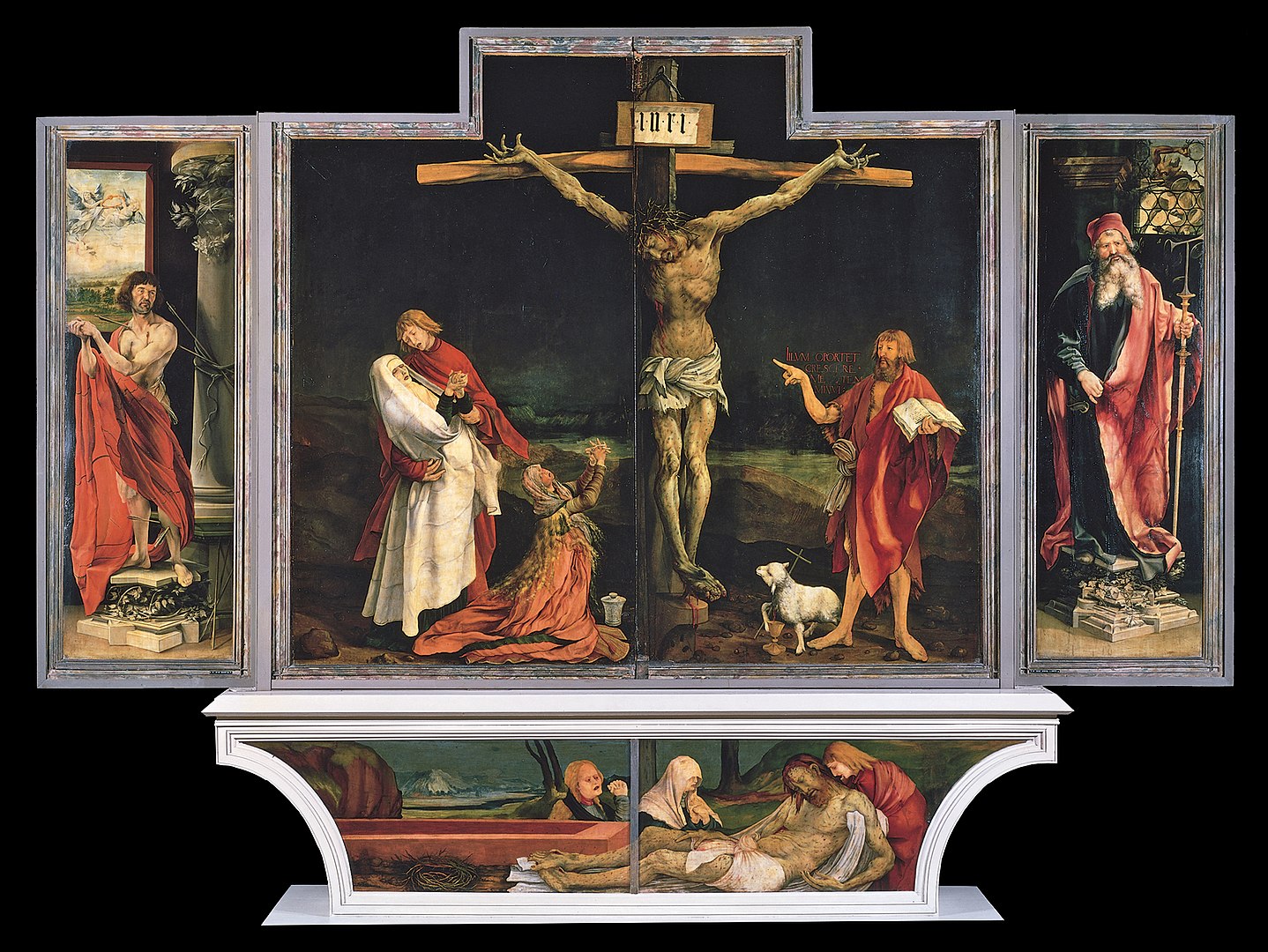

“The Crucifixion”, the central scene of the Isenheim Altarpiece, c. 1510-1515

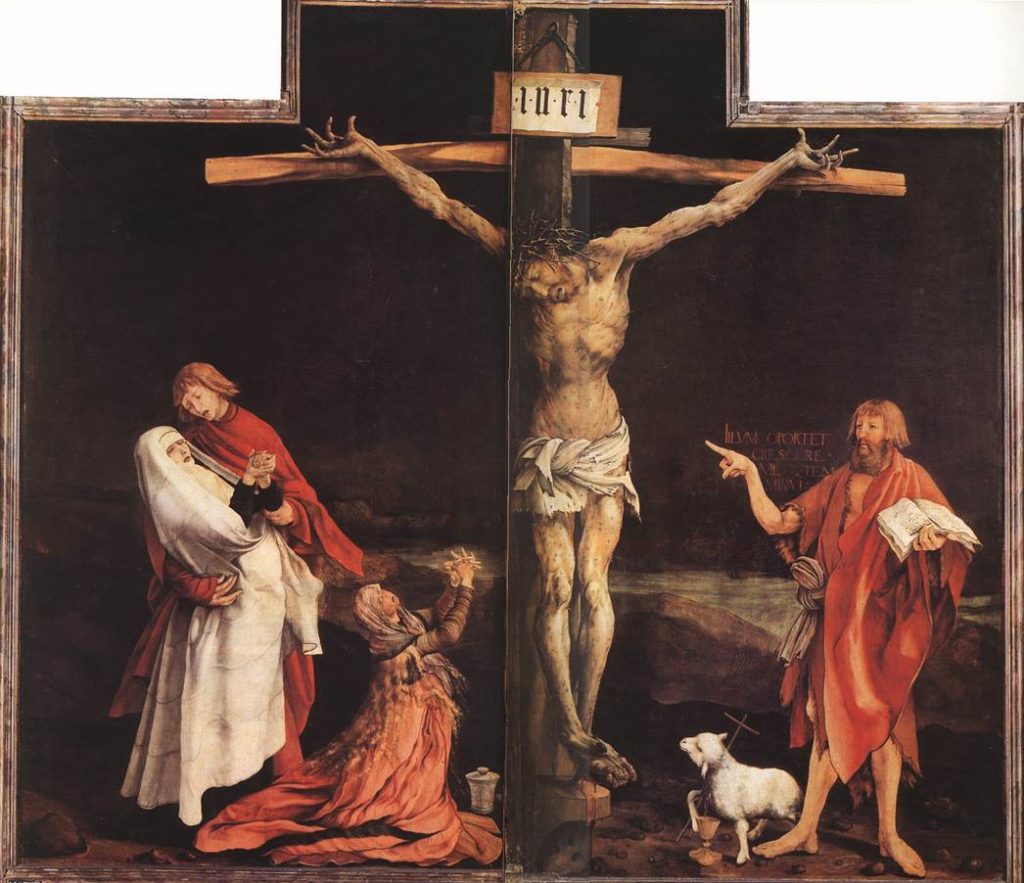

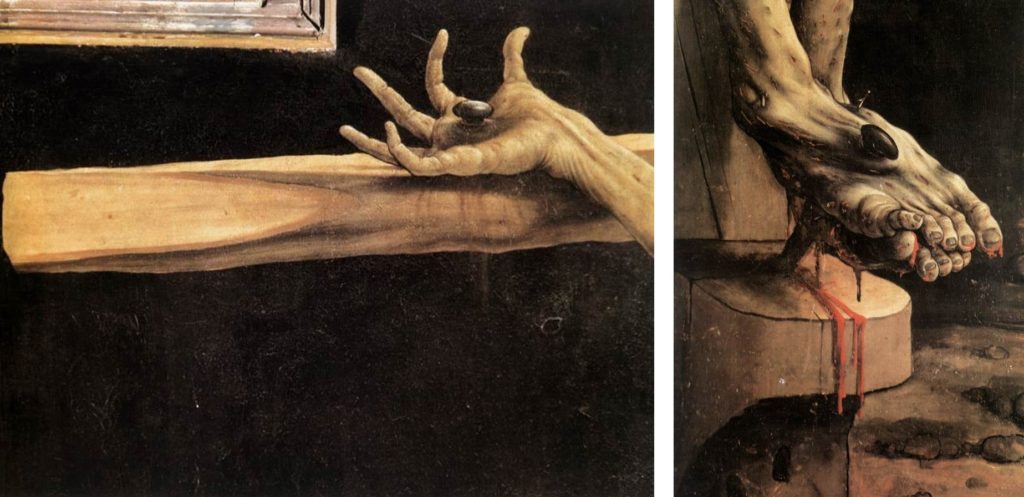

Christ’s body is absolutely material – the wooden cross bends to bear its weight. Jesus’s lips are blue; His tortured flesh seems greenish. Festering pierced wounds cover the skin of the Son of God. Blood trickles from the gash in His side.

He’s suffering – His curved ankles and splayed fingers testify to intolerable physical pain. Raised to the sky and held by nails, the hands of the savior appear to be unnaturally large.

With no less persuasiveness, the artist showed the experience of witnesses to the execution – the Mother of God, St. John, and Mary Magdalene.

Mary Magdalene, kneeled at the foot of the cross, desperately stretches out her hands to Jesus – as if she were sure that he no longer hears her.

St. John, the Christ’s disciple who is to write one of the Gospels, comforts the Virgin Mary. His gesture is not simply an instinctive impulse to support someone who doesn’t feel well. Already being crucified, Christ took care of the fate of His grief-stricken mother. “Here is your mother”, he said to the young man. St. John fulfills the last will of the Teacher. His attention is completely turned to Mary.

Our Lady is almost fainting. Her pale face resembles the face of a dead person. The snow-white veil she is wrapped in reinforces the impression. She actually died in a sense: her child has killed in front of her eyes.

Only John the Baptist, depicted on the right, appears strangely unemotional. There is an explanation for his reticence, though. By the time of the death of Christ, he was not alive; he could not personally observe the scene of the crucifixion. The presence here of John the Baptist – the Jewish prophet who baptized Christ – has a purely symbolic meaning.

The saint points to Christ. The Latin inscription next to the prophet’s arm means “He must increase, but I must decrease”. There is no doubt that the artist encourages us to think seriously about the growth of Christ and the diminishing of mortals. We even have reason to assume that the panel serves as a kind of illustration for St. John the Baptist’s words.

All the figures are located almost on the same line, but the figure of Christ juts forward. It is significantly bigger than the others.

The background corresponds to the general mood of the work. The painter eternalizes one of the scary moments of those three hours, during which, according to Scripture, the sun over the Calvary was swallowed up by thick gloom.

The red clothes of the saints and the white Blessed Mother’s veil look unpleasantly bright against a dark background.

Sixteenth Сentury Expressionist

The emotional charge of The Crucifixion is so powerful that the talent of its creator was admired by expressionists, recognized experts in conveying strong feelings.

However, in the 16th century, nobody considered him either a genius or an innovator. Сontemporaries perceived him as quite a conservative painter committed to medieval traditions.

While his compatriot Albrecht Dürer produced self-portraits and nature studies, he continued to concentrate on biblical subjects. The artistic tricks he used were not new, for the most part. Changing the size of figures depending on their significance, say, is a very old rule of religious painting – so old, that it was considered outdated when our painter started to work at the Isenheim Altarpiece.

Little is certain about this man. We know neither the exact date of his birth nor his name. The authors of popular encyclopedias usually refer to him as Matthias Grünewald, yet many art historians believe that it would be correct to call him Mathis Gothart Nithart.

Regarding the circumstances in which the altar was created, we can judge them with sufficient confidence. They are one of the keys to understanding the terrific effect of this The Crucifixion.

Torment Can Make Sense

Master Mathis created the altar for the chapel in the monastery of St. Anthony at Isenheim. The service of the monks who lived there consisted not only of praying.

The monks of the Antonite order were basically medics, and not just medics, but, as we would say today, subject matter specialists. They treated people infected with ergotism – a gangrenous poisoning.

For the most part, ergotism was a sentence to a slow painful death. Those few who recovered often remained disabled, since the recovery was achieved at the cost of amputation of one or more limbs.

The set of the symptoms through which this disease manifested itself included shedding the outer layers of the skin, body tissues becoming black and putrefying, distorted joints, and hallucinations.

The agony in which Christ is writhing in the Crucifixion by Master Mathis is extremely similar to the torments of those stricken by ergotism. Only such a Christ could awaken compassion in their souls. If these sufferers managed to keep deep faith in the Son of God dying for people, they also kept faith in the Risen Savior.

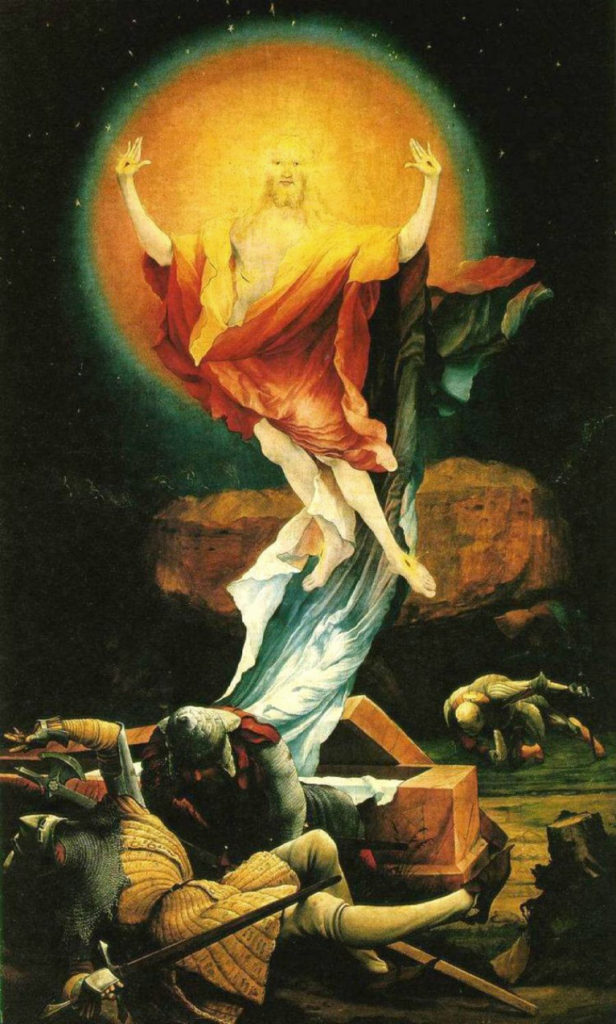

A vivid image of the latter is painted on another side of the altarpiece, on the wing.

Christ soars above the tomb, and behind him, like a trail of light, stretches a shroud in iridescent reflections of the halo.

The guardians, blinded by the blast of light, flounder helplessly under the weight of their chain armors. These people have no chance to stop the spread of the majestic radiance. It will inevitably dispel the darkness.

- The Story of Art – Ernst Gombrich, Phaidon, 1950

- How to Understand a Painting – Françoise Barbe-Gall, Frances Lincoln Publishers Ltd, 2011

- ART: a visual history – Robert Cumming, DK, 2020