Greatness and calmness – here are two words that accurately describe the Paris Panthéon. Located in the very heart of the lively Latin Quarter, this edifice is alien to hustle and bustle. It is in another dimension.

The Church of Saint Genevieve

There is a cross on the top of the Panthéon’s dome. It is not hard to guess that the building was originally a church.

In 1744, King Louis XV was taken seriously ill. The king didn’t believe doctors would save him. The monarch prayed for the assistance of Saint Genevieve, the heavenly protector of Paris. Louis vowed that if he recovered, he would erect a new big temple to house her relics in it.

Louis XV did recover. The king kept his promise, albeit with considerable delay – ten years passed before he started to seek an architect who could design a truly grand church.

The choice fell on Jacques-Germain Soufflot. He got down to business with enthusiasm. Nevertheless, work proceeded very slowly. The construction required significant financial investments, sometimes far more significant ones than Louis was able to afford. Neither king nor the architect lived to see the Church of Saint Genevieve in all its glory. A pupil of Souflott, Jean-Baptiste Rondelet, finished this ambitious project in 1790.

The sarcophagus with Saint Genevieve’s relics was placed in the crypt.

The Temple of Patriotism

By the time Rondelet completed the church the French Revolution had begun. As it usually happens as the wind of change is blowing, people have rethought their attitude about God.

Atheists appeared. St. Genevieve’s relics were destroyed – only a few remaining fragments survived… However, not everyone behaved so radically. Most of the enlightened Parisians adhered to deism.

Deists asserted that God had created the universe and then left it. The task of man, in their opinion, was to learn the natural laws of the world and live according to them. The era of rationalism has come.

The temples of science, justice, and art started to play almost the same part as churches had played.

The church of Saint Genevieve received the status of a secular mausoleum. It got the name the Panthéon after the Roman Pantheon where some great Italians are entombed.

In 1790, the ashes of the Comte de Mirabeau, a leader of the early stages of the French Revolution, were solemnly brought into the former church.

Less than a couple of years later, Jean-Paul Marat and Maximilien Robespierre found evidence of Mirabeau’s secret connection with the royal court, and yesterday’s hero turned out to be a traitor. His remains were taken out of the Pantheon and buried in the graveyard for criminals. A similar nasty story happened with the remains of Marat himself soon after.

But the philosophers Voltaire and Rousseau’s ashes, placed in the Panthéon in the last decade of the turbulent 18th century, are still there.

The Mausoleum for French Luminaries

The Panthéon was twice converted back to a church and secularized during the 19th century.

Its fate was finally decided in 1885 when Victor Hugo suddenly died. The death of the towering figure in French literature, a great defender of liberty, generated unprecedented national mourning. It would be strange to bury Hugo in a cemetery. His remains were buried in the Panthéon and provided the building the constancy of its status.

Since then, the Panthéon became the last shelter to many luminaries – writers, scientists, and public figures.

The inscription on the frieze of the building reads “Aux grands hommes la patrie reconnaissante” (A grateful nation honors its great men).

The Building Reflecting its Age

In stark contrast to the sumptuous pediment of the Panthéon, its walls are barely decorated. “The architect didn’t have enough money to decorate them,” we may say. “Fine reliefs would make these huge empty areas far more attractive.”

The viewers of the 18th century had a slightly different opinion on this matter. Tired of the frivolous pomposity of Baroque and Rococo, they tended to enjoy noble simplicity.

If we could ask Parisian intellectuals of that period which building, in their view, is the ideal example of architecture, they would probably name an Ancient Greek or Roman temple. Classical edifices with their clean lines and strict proportions perfectly corresponded to the rational spirit of the Enlightenment.

Jacques-Germain Soufflot – the architect who designed the Panthéon – not only admired Classical antiquities yet also knew them very well. He had studied architecture in Rome, examined the excavations at Herculaneum, and visited Paestum to see the best-preserved Greek temples.

Of course, Soufflot modeled his life’s work after the principles of Ancient architecture. The Panthéon became one of the first Neoclassical buildings.

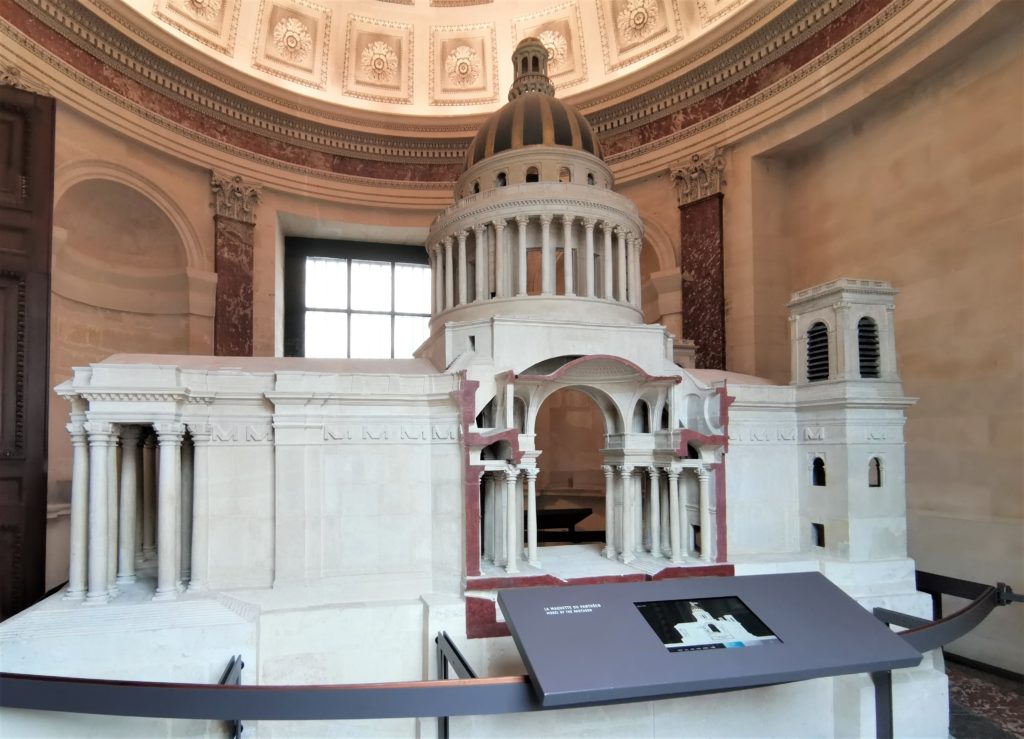

The main feature of Ancient Greek architecture in the appearance of the Panthéon is its elegant portico with Corinthian columns (such a column is easily recognizable due to the tongue-like leaves forming the capital), a peristyle with a triangular pediment on the main facade, and the imposing dome.

The building also has some features atypical for Ancient Greek temples, though: being a man of the Enlightenment Age, Soufflot liked experiments. He combined the principles of classical and Gothic architecture.

The interior of the Panthéon feels airy like an interior of a Gothic church, chiefly thanks to slender columns on which the dome rests.

These columns can hold the massive vault because Soufflot strengthened the stone structure with a system of iron bars. Nowadays, using reinforced constructions is a common trick; at the epoch of Jacques-Germain Soufflot, this was a bold innovation.

The fresco inside the dome depicts The Apotheosis of Saint Genevieve – in a sense, the Panthéon is still a church dedicated to the patroness saint of Paris.

The story of Saint Genevieve’s life is also represented on the walls. These pictures look unexpectedly bright. They aren’t frescoes but oil paintings, indeed.

The artists, who decorated the temple in the 19th century, worked in the technique of marouflage – they painted each scene on a canvas and affixed it to a wall.

When I was in the Panthéon, I’ve photographed this picture portraying Saint Genevieve on her deathbed:

Just look – the old sick woman isn’t waiting for sympathy or help. On the contrary, she’s the strongest person here. The adults and the children surrounded her to ask for her support. I stood in front of this picture for a long time.

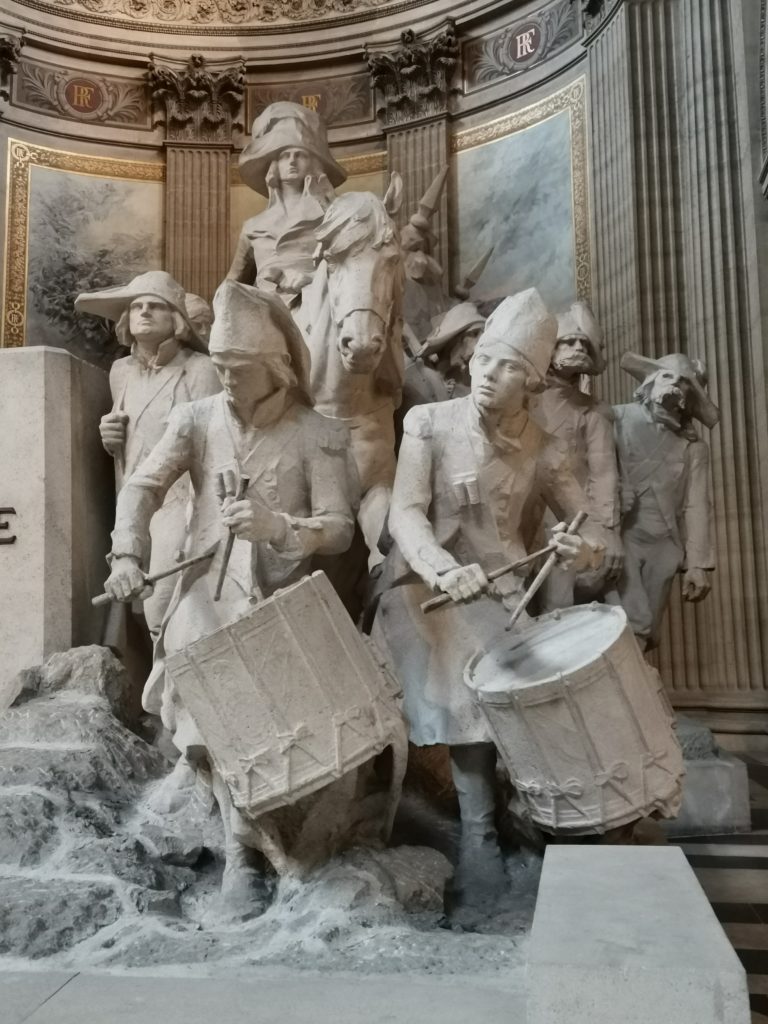

The major sculptural composition of the Panthéon – La Convention Nationale – impressed me as well.

The monument references the harsh days of the French Revolution (La Convention Nationale was the first French government). In the center of the composition, a gorgeous, triumphant female figure rises – the symbolic embodiment of the free Republic. The deputies are stretching out their hands to her, the soldiers are going to struggle for her.

All the faces are smart and decisive. Only the young drummer is looking into the future with surprise, perhaps even fear.

- Architecture: The Whole Story – edited by Denna Jones, Prestel Publishing, 2014

- Анатомия архитектуры – Семь книг о логике, форме и смысле [The Anatomy of Architecture – Seven Books on Logic, Form and Meaning]- Сергей Кавтарадзе, Издательский дом Высшей школы экономики, Москва, 2020

Great article with beautiful pictures. It was interesting to read. Keep up the good work 🙂

Thank you so much!)

Very interesting.

Good to know. Enlightenment.

Great info, thank you. Last April I went to Washington DC where I discovered that the US capitol was built using the French pantheon as a model. The city was designed by the French engineer Pierre Charles L’Enfant. Imagine that!

Thank you for the interesting information!

I am French, but the best article on the Panthéon is by far that one!

It’s beautifully written, clear and very interesting. 😉

Thank you very much! France is a very inspiring country.

Great work! I been in Paris and loved the city and it’s architectural buildings. Best, artists rows where you could buy paintings from aspirants artist. Looking forward seeing further articles good luck!

Thank you, Ruben! My blog means a lot to me; I hope I will write many new articles and publish them here)