“I died for beauty, but was scarce” conjures up pictures linked with the macabre physicality of death – the narrator is a decaying corpse. This poem should be frightening and unpleasant…

It attracts, even comforts the reader though.

Three Great Stanzas

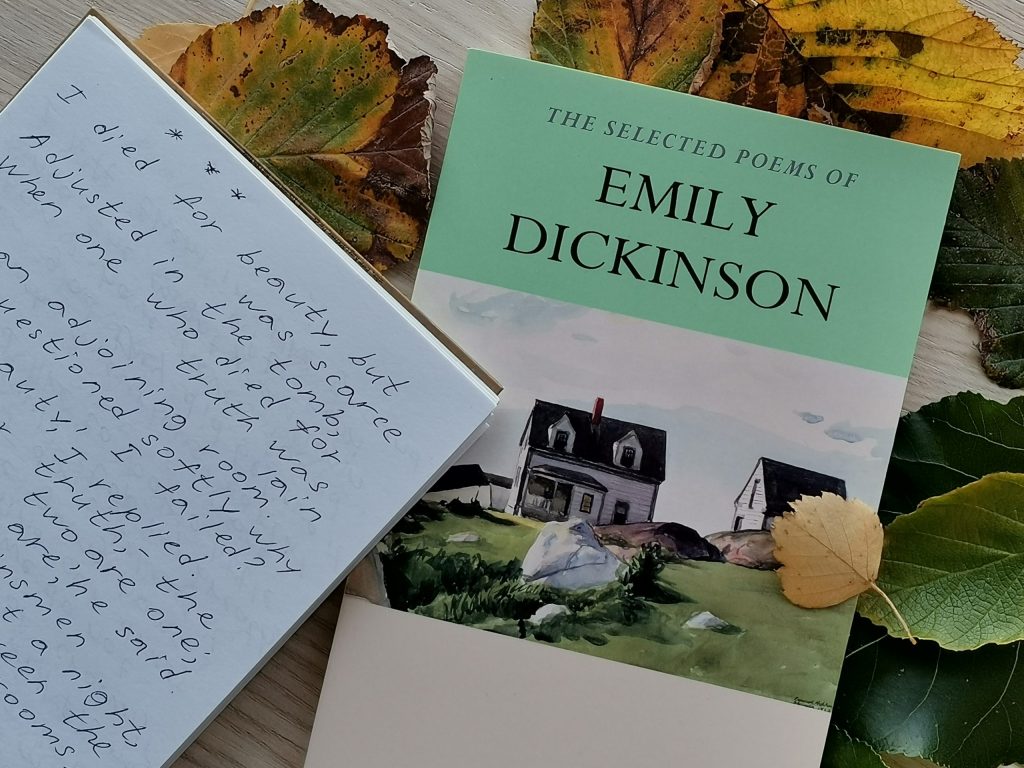

For a start, listen to the poem. Don’t be surprised, you will hear a man’s voice. “I died for beauty” is one of the pieces in which the gender of the narrator matters little.

The voice is accompanied by Dickinson’s written text in a standardized edition.

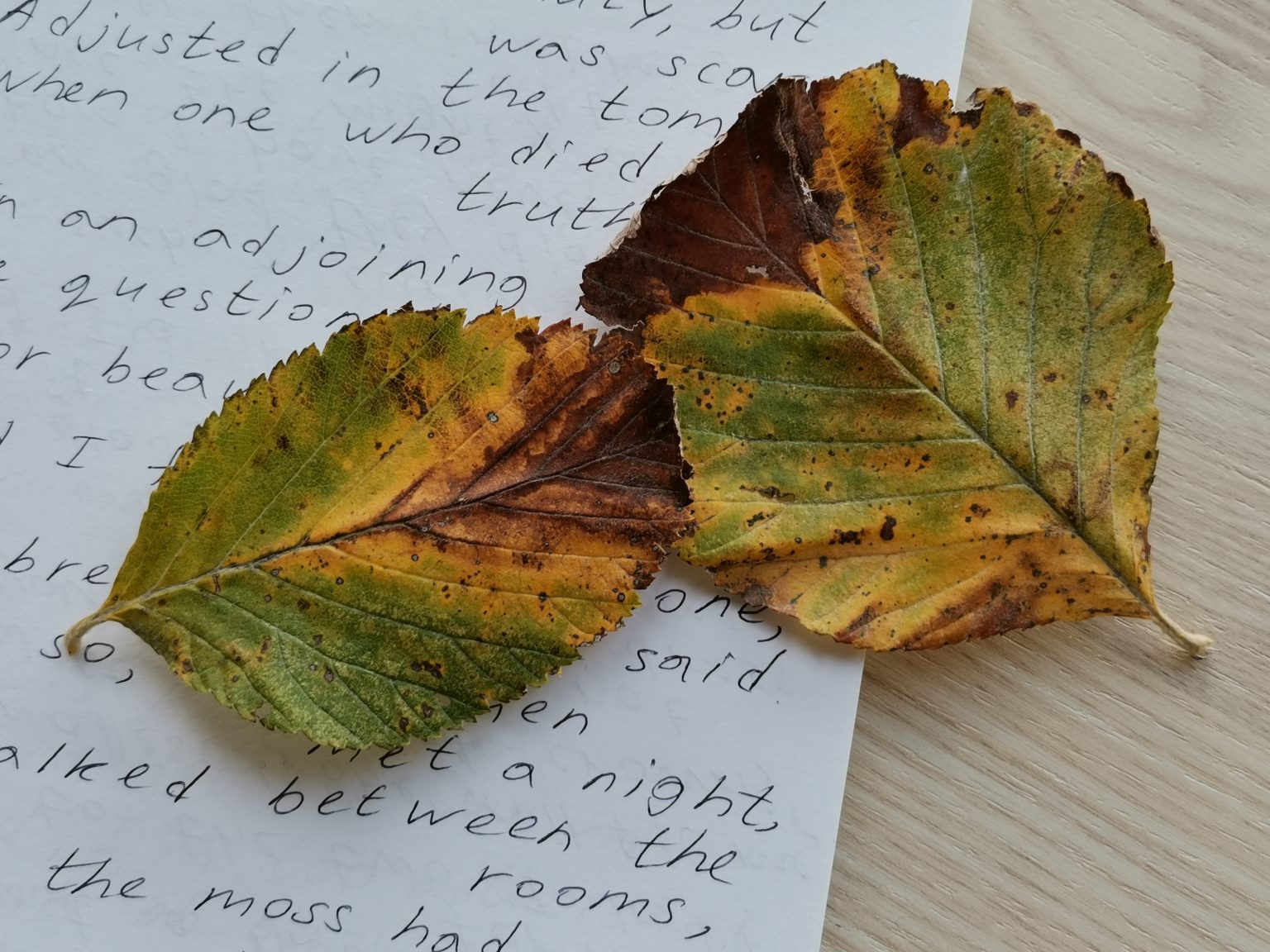

I also offer you the chance to read the poem with the original capitalization and punctuation – Emily Dickinson usually purposefully omitted commas, semicolons, and periods; she replaced them with dashes:

I died for Beauty—but was scarce

Adjusted in the Tomb

When One who died for Truth, was lain

In an adjoining Room—

He questioned softly “Why I failed”?

“For Beauty”, I replied—

“And I—for Truth—Themself are One—

We Brethren, are”, He said—

And so, as Kinsmen, met a Night—

We talked between the Rooms—

Until the Moss had reached our lips—

And covered up—our names—

Close your eyes for a moment. Your thoughts about these lines may turn out to be more important to you than everything I’ll write below – because they are your own.

Attempt to Understand the Incomprehensible

Two noble people perished for high principles; their corpses decayed; their names on the gravestones worn away. Dickinson shows that every aspect of human life, from ideals to identity, is erased in time.

She uses an unexpected synonym for the word “died” – her narrator “failed”.

Pay attention to when and how the word appears in the text. It is a part of the question that helps the newly entombed to strike up the conversation. The speaker hasn’t observed the death of his random neighbor’s death; nevertheless, he asks, “Why you failed?” instead of the more logical, “Have you failed or succeed?” The fact of failing is taken for granted. The defeat is death itself.

There’s another possible interpretation of the unusual synonym. Fighting for Beauty and Truth (notice the awe-inspiring uppercase letters!), the two just couldn’t achieve total victory. A mortal being cannot turn the real world with its various contradictions into the perfect paradise. This is an eternal tragedy of human existence.

And now, the most surprising thing: despite the author speaking about a tragedy, the mood of the poem isn’t sorrowful at all.

Our martyr is telling their story in a restrained, almost indifferent tone. The actions are recounted without any emotional epithets or exclamations of despair. It seems that One who died for Beauty and the narrator are two different entities… They really are.

In the poem, “I” is both the body and the soul of the entombed.

The body, in a sense, still belongs to life. It remembers the past; it is afraid of oblivion and needs to have a like-minded friend. The soul already got away from all earthly values. It isn’t interested even in Beauty or Truth. What is significant to the soul? Nobody knows.

Emily Dickinson passionately tried to solve this riddle in her poems. She very often wrote “about the moment of death, the presence of death, and tombs” (1).

As Dickinson’s biographers note, the poet attempted to learn it as a phenomenon: in her letters, Miss Dickinson requested her correspondents who witnessed death to describe the process of dying. The amazing woman wanted to know what people feel in their final hours, whether or not they are calm.

She believed in God, and apparently in the afterlife, but this belief was not a safe haven for her.

Gilbert P. Voigt writes about Dickinson’s religious attitude (2):

“One moment she is not sure there is another life; another time she is certain of it. On one occasion she accuses God of duplicity; on another, she expresses “perfect confidence in … His promises.” Sometimes He seems a cruel enemy; again, an infinitely tender friend.”

The courage to doubt assumed truth, and the stubborn endeavor to explain the incomprehensible – true poetry always begins from these.

- Critical Essay on “I Died for Beauty” – Jennifer A. Bussey, Poetry for Students, Gale, Cengage Learning, 2008.

- The Inner Life of Emily Dickinson – Gilbert P. Voigt, College English, Vol. 3, No. 2, November 1941, pp. 192-96.

It is The interpretation that makes the text fascinating and alive.

Meanings brought to light, which otherwise would remain hidden.

Thank you for reading my article! I’m glad that you found it interesting.

Another brilliant article. I have tried but can not get into poetry. You changed that! You need to write a book. 100 poems with your analysis!

Thank you for the kind words, Chris! Maybe, someday I will actually write a book of that sort.