“Either I’m wrong, or The Queen of Spades is really a masterpiece,” Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky remarked in a letter to Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich. Unfortunately, I have no idea what he answered the composer. But if I were in his place, I would write in capitals: “Pyotr Ilyich, you are absolutely right!”

Two Destinies of One Character

This tragic opera was born out of an anecdote.

Prince Sergei Grigoryevich Golintsyn once told his friend Aleksandr Sergeyevich Pushkin a story about his relative, an old countess: she allegedly knew three cards that ensure a guaranteed win.

Pushkin found a literary application even for the high society gossip as a writer by vocation. He created the gripping short narrative The Queen of Spades.

Its main character, the officer named Herman, dreams of becoming rich and has a penchant for gambling yet feels too prudent to rely on luck. Having accidentally heard that a countess is aware of a reliable way to win at cards three times in a row, Herman decides to ferret her secret out.

He enlisted the sympathy of the countess’s companion, Lisa. The girl agrees to a date with Herman and gives him the key to the house so that the young officer could visit her at night.

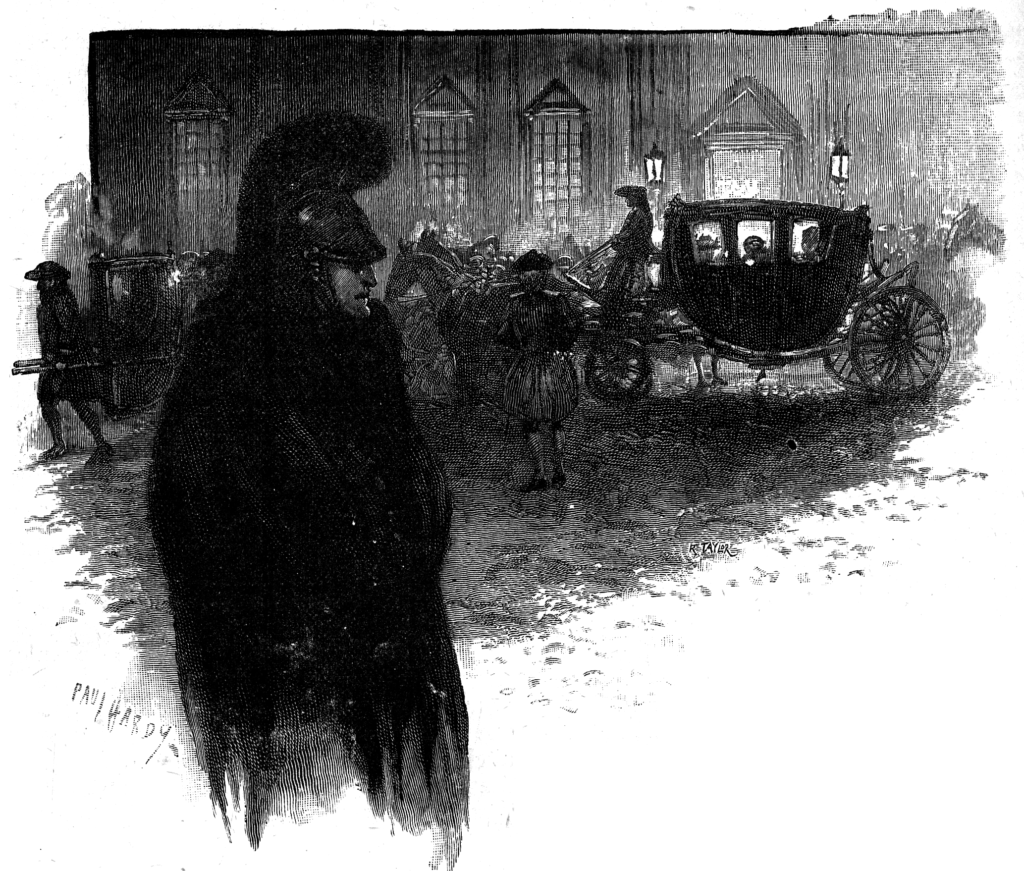

Herman hides in the сountess’s bedroom. When the countess returns to her room, he comes out of hiding and begs her to let him in on the secret. The old woman is speechless from fear. Herman draws his pistol. The countess becomes unwell; she dies.

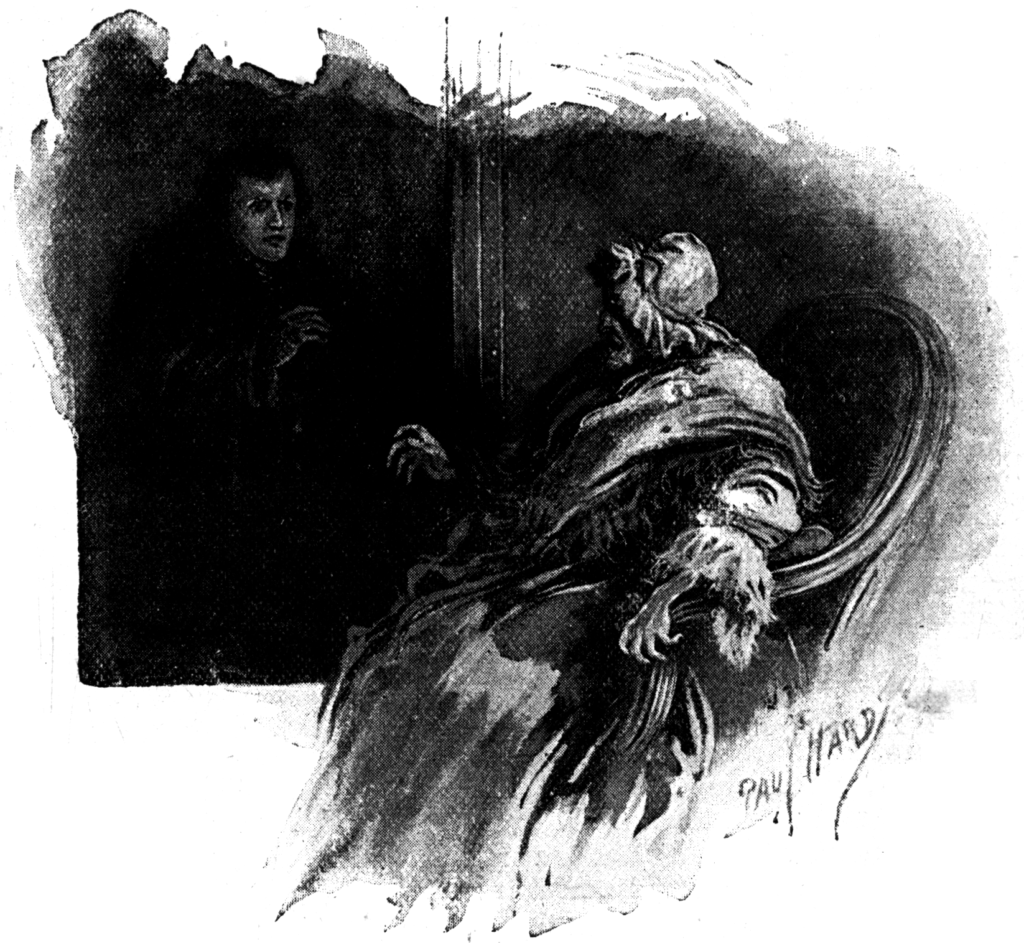

A few days later, however, the ghost of the countess appears to him. She says that the cards that will help him win are three, seven, and ace. Herman does win twice. Then he somehow pulls out the wrong card – a queen of spades instead of an ace. The queen of spades looks precisely like the deceased crone… Herman loses his modest savings and goes crazy.

In the late 1880s, the Director of Imperial Theatres asked Tchaikovsky to compose the opera based on Pushkin’s The Queen of Spades. At first, the proposal did not interest Pyotr Ilyich: the plot was too prosaic.

However, he changed his mind after a while and got the job. The author of the libretto was Tchaikovsky’s brother Modest Ilyich. He became interested in the work and gradually involved Pyotr Ilyich in it.

To add deep feelings to the opera, they made Herman fall in love with Lisa.

Love, as usual, changed everything, including the composer’s attitude to the project. He left all his affairs and began to write music for The Queen of Spades for days on end in some kind of feverish state.

The three-hour piece of music was created in the shortest possible time: the composer prepared it for the opening of the next opera season.

Tchaikovsky was truly fascinated: besides the music, he wrote the words to some fragments, particularly Liza’s aria from the last act.

Neck or Nothing

Brothers Tchaikovsky rethought the image of both Herman and Liza.

According to the libretto, she is a wealthy bride, the granddaughter of the Countess. Lisa is already engaged to a Prince Yeletsky.

Yeletsky is in every sense a wonderful groom. He is rich and noble; he loves Lisa and cares about her well-being. The problem is that ardent Herman captures Lisa’s heart.

Herman is deprived of the opportunity to claim the girl’s hand because of his poverty. Nevertheless, he does not want to accept his destiny.

“She will be mine – or I will die,” the young man states.

Lisa has to choose, and she chooses poor Herman. Liza gives him the key and says that he can go to her through the Countess’s bedroom at night. The Countess’s bedroom! Herman takes these words as a sign of fate. The stakes are raised: now Lisa’s love is not enough for him; he can learn three cards, win a large amount and ensure a comfortable future for himself and his beloved.

Herman seems to forget that Lisa will be waiting for him

He made his choice, he preferred the meeting with decrepit crone to the date with “belle, goddess, angel”.

Herman’s soul yearns not for love, but passion, any all-consuming feeling.

While hiding in the Countess’ room, Herman admires a portrait in which the Countess is depicted as a young beauty, reckless and overbearing.

“I stare at you and hate you, But my eyes can never feast their fill!” – Herman exclaims and adds in a terrible foreboding, “One of us is destined to perish from the other!” The old woman dies in the same way as in Pushkin’s story – silently.

“She is dead and I haven’t learned her secret!” – Herman shouts repeatedly. Terrible wind instruments echo his desperate cries.

Herman and Liza are doomed. The old woman will drag them along: that’s who the real player is.

The old woman’s part is the most interesting in the opera; Herman’s one is the most difficult.

Its performer must have impressive acting talent. During the scene in the bedroom of the Countess, Herman is already so obsessed that a greater obsession appears to be no longer possible; the most expressive notes have been struck.

But the performer of his part must still sing the whole third act, demonstrating the greater and greater madness.

Fatal Petersburg

In the Russian language, the words denoting passion and suffering – “страсть” and “страдание”, respectively – are linguistically related. In the Russian mind, they also cling to each other.

One of the performers of the part of Liza, Lyubov Kazarnovskaya, in an essay on The Queen of Spades remarks: “We Russians are never completely happy. (…) We are always looking for suffering and always suffer – this is our innate character trait.”

She repeats the idea of the gloomy genius of our literature Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. Tchaikovsky, by the way, simultaneously loved and hated Dostoevsky (just like Herman the Countess a few minutes before her death!).

Although the composer sobbed sweetly in admiration over The Brothers Karamazov, he admitted that Dostoevsky unbearably weighs him down.

During his work on The Queen of Spades, Tchaikovsky himself unexpectedly turned into Fyodor Mikhailovich – an expert on all the disastrous and dark that is typical of the Russian character.

St. Petersburg with its restless white nights, gray days, and morbidly nervous eccentrics obsessed him.

In Petersburg, Tchaikovsky’s characters love and die. Lisa jumps into a canal. As the libretto says, “in the distance can be seen the embankment and the fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul in the moonlight.” Herman, whom the merciful Pushkin allowed to live out his remaining years in a lunatic asylum, in Tchaikovsky’s opera, mortally wounds himself next to a gaming table.

The opera ends with a church choir singing, also very Russian. Any earthly passions dissolve in it without a trace.

Who is at fault?

The hopes of all the main characters of the opera are dashed. Why? Is it true that mystical evil fate is the cause of such a sad denouement?

The answer to this question we will find in music.

If we try to define the style in which The Queen of Spades is composed, we won’t be able to do this. It consists of completely heterogeneous fragments – Orthodox funeral chant, Russian folk song, French opera music, a motive similar to a march, and many others. These different styles do not overlap with each other at all.

It is also significant that there are very few dialogues in the opera: a chain of monologues forms The Queen of Spades.

Throughout the opera, the characters do not hear each other; they live in separate closed realities.

Lisa tries to get into Herman’s reality but to no avail. A little earlier, another person, Yeletsky,

attempted in vain to get into her world and she did not respond with a single word to his long fervent speech (“Wait one moment! I simply must speak to you! I love you, love you beyond all measure, I cannot conceive a day without you, I am ready to accomplish for our sake A heroic task requiring matchless strength” and so on).

The quintet “I feel afraid” is the only fragment in which the emotional states of the main characters at once – Liza, Herman, Yeletsky, and the Countess – coincide. Alas, nobody of them notices someone else’s pain even in it.

The Queen of Spades is scary, and the scariest thing in this opera is not the mystic three cards.