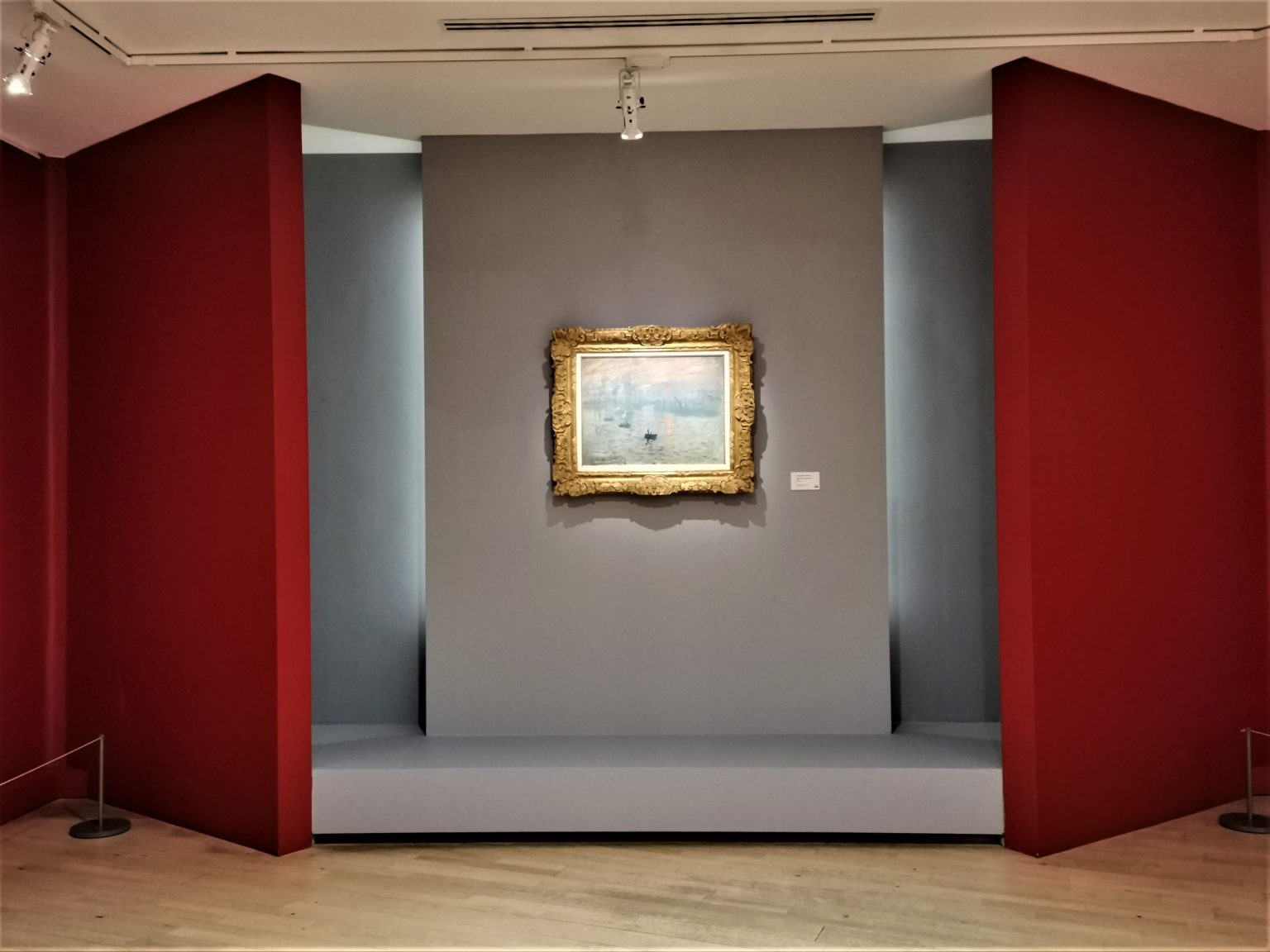

There is an interesting exhibit in the Musée Marmottan Monet – a little oil painting hanging alone on a wall. The bench put in front of this wall appears to invite the viewer to have a seat and think carefully about the work.

The picture represents a misty morning in a port. Its strokes are bold; its colors are pleasing to the eye. It is hard to believe that such a nice painting, as well as many other works similar to this one, drew harsh criticism just a century and a half ago.

Monet’s Quiet Debut

When Oscar-Claude Monet first started his career, the Parisian Academy of Fine Arts confidently set the tone in Western art.

The Academy regularly organized the greatest art event that shaped public taste – the official exhibition named Salon. It let recognized painters sell their recent works and provided talented beginners a chance to be noticed.

Not every painter was able to offer works that could meet the strict standards of the Salon jury. The learned society welcomed only those who applied a highly finished technique without any visible strokes. With regard to the subject matter, preference was given to uplifting mythological and historical canvases. Portraits and landscapes were also considered acceptable – on the condition that the artist idealized the model or nature.

Claude Monet initially attempted to achieve success in the conventional way – through Salon. He painted two “right” works – the first of them depicted a seaside scene (see the picture below), the second portrayed boats on the mouth of the Seine.

In both paintings, Monet refrained from any obvious hint of modernity. The works were rendered in relatively dark hues befitting a serious painting and featured elaborated details.

These landscapes easily passed the qualifying stage and were presented at the Salon of 1865. The press found them as favorable as the Academy. A critic wrote in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts about Monet’s “‘feel for color harmonies in an interplay of related tones” and “his daring way of seeing and of enforcing our attention.”

The Success is Close

Monet’s debut was successful, albeit not really bright. At the next salon, he submitted a full-length portrait of his mistress Camille Doncieux – The Woman in a Green Dress.

The academicians and critics highly praised the artist’s handling of the fabric in which the model’s dress was made. Some experts even compared Monet with the old masters.

Was this a lovely painting? Definitely. Was it a true work of Monet – such a work that fully embodied his character and talent? No, not yet.

The Big Fail

Spurred on by his achievements, Claude Monet began to paint a huge canvas that would depict many life-size figures at once, Luncheon on the Grass. Sadly, the work was interrupted – Monet had no money for rent and he gave the half-ready piece to his landlord in lieu of payment.

The artist started a slightly smaller figure painting – Women in the Garden:

The piece cost him dearly; it took a lot of effort, time and money (oil paints are an expensive medium, especially if you want to cover the canvas measuring 2,5 by 2 meters).

He did not have to spend money on models at least – Camille patiently posed for all four female figures.

The committee of the 1867 Salon rejected the painting because of its futile subject and careless brushwork.

In truth, the jury had good reason to criticize Women in the Garden. The women depicted in this painting resemble dolls devoid of any individuality. But Monet’s focus was not the people and their unique characters; his focus was light.

From the very beginning, Monet was determined to paint Women in the Garden outdoors. He worked in the park as long as the weather remained warm enough, intending to finish the picture outdoors.

His choice was not traditional. Monet’s predecessors and contemporaries considered plein air techniques suitable solely for preliminary sketching. The true landscape was almost always composed and completed in the studio.

Monet did not manage to finish his big picture before winter yet his approach to the work gave an unexpected result: the artist discovered the exhilaration in painting what he saw instead of what he should see.

The following year, Monet didn’t try to please the Academy with a correctly composed picture. Rather, he painted alive and modern Paris with his friend Pierre Auguste Renoir. Sunlight flooded Monet’s canvases.

Impression in Le Havre

Monet worked quickly, capable of creating a picture in only a few hours.

While visiting his hometown in 1872, the artist painted a series of study-like pictures. The six landscapes portrayed the modern port at different times of the day. The artist painted this piece in the early morning:

Monet created it from the window of his hotel room.

There are silhouettes of rowboats in the foreground; the tall masts of clipper ships are visible in the distance. The sun rises.

The landscape with no details and loose brush marks looks unshaped. Nonetheless, the overall depiction is convincing. A human eye lacks the precision of a photo camera. We usually note only the outlines of objects and ignore their precise features.

Monet strived to convey the quietness and the coolness of the hazy morning in the port focusing on the feeling. He masterfully combined complementary colors. Calm blue perfectly conveys the atmosphere of the dormant harbor; energetic orange heralds the bustling day.

Claude Monet entitled his work simply Impression, Sunrise. The artist later remembered that he titled it in haste, “They asked me for a title for the exhibition catalogue, it couldn’t really pass as a view of Le Havre, so I said: ‘Put Impression.”

At this time, the only authoritative exhibition was held by the Salon. But Monet and Salon have already parted ways by this point… Where was he going to show his works?

The Alternative Exhibition

Monet had several friends who were also painters: Pierre-Auguste Renoir (previously mentioned), Camille Pissarro, Alfred Sisley, etc.

These artists, for the most part, fairly young ones — spent a great deal of time together. They met in Parisian cafés and discussed their creative ideas. None of them were content with the academic standards of painting.

The friends were not interested in depicting mythological scenes, but life in all its fickleness.

Since their goals were similar, their techniques had a lot in common as well. They worked with bold strokes and simplified the forms, avoiding strong lines and black shadows.

Monet became the informal leader of this circle.

As a consequence of their talks, the young painters decided to organize their own separate exhibition.

It opened on 15 April 1874, in the center of Paris – the photographer Nadar allowed the artists to use his studio. The group was in no way positioned as revolutionary; the artists of the new creative generation just sought an opportunity to show the public their works. They described themselves very formally – the Cooperative and Anonymous Association of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers.

Fortunately, this awkward name sunk into oblivion very quickly.

The Defeat That Ended in the Victory

The first exhibition of Monet and his friends’ paintings failed miserably. The public was reluctant to visit it. The art critics came to Nadar’s studio and then wrote about the presented pictures, yet how they wrote! They seemed to be competing in backbiting.

Monet’s exhibition of Impression, Sunrise with its sketchy style turned out to be one of the most convenient targets for mockery.

In the satirical magazine Le Charivari, the critic Louis Leroy published an article in the form of a dialogue with the artist Joseph Vincent.

The dialogue included the following remark characterizing Monet’s picture:

What is this painting of? Look in the catalogue.’ ‘Impression, Sunrise.’ ‘Impression– I knew it. I was just saying to myself, if I’m impressed, there must be an impression there… And what freedom, what ease in the brushwork! Wallpaper in its embryonic state is more finished than this seascape!

Having borrowed the word from the painting’s title, Leroy headed his article ‘’The Exhibition of the Impressionists.

This definition was rapidly adopted by the other journalists and by the artists themselves. After all, they didn’t see anything wrong in conveying feelings on the canvas.

The so-called ”pariahs of the Salon,” another expression from Leroy’s review, did not give up on the idea of exhibiting their works independent of the Salon, nor did they stop painting them.

The liberty and power that the new style gave these artists rewarded them despite the rude taunts.

The whole world offered them its plots. They could paint everything and everywhere without worrying about whether their works were viewed as right or not.

There were eight Impressionist shows between 1874 and 1886. Little by little, the public became interested in the ‘’pariahs.” The first exhibition drew no more than 3,500 visitors in total; the final show attracted about 500 visitors a day.

Impressionist exhibitions irreversibly undermined the near-monopoly of the Salon and encouraged hundreds of aspiring artists around Europe. Favorites of the Academy began to lighten the palette of their works: accustomed to the sunshine of Impressionist paintings, the public no longer bought solemn, dark paintings as readily as before.

As for Claude Monet, he no longer had to puzzle over how to pay for canvases and paints.

- Claude Monet – Christoph Heinrich, Taschen, 2019

- Impressionism – ed. Ingo F.Walther, Taschen, 2016

- Art History – John Finlay, Arcturus, 2020

- The Art Book – DK, Penguin Random House, 2017

Claude Monet had a difficult beginning. That’s normal. But he stuck on and that lead him to success as the protoganist of a movement, the Impressionism.

Perseverance pays.

Yep