Many great Romantic composers were great humanists. Let’s recall, at least, Schubert and his ability to sympathize with people: his Der Leiermann is a desperate lamentation for the loneliness to which each of us is doomed one way or another.

Austro-Bohemian Romantic composer Gustav Mahler was a humanist too. However, unlike gentle Schubert, Mahler expressed his love to mankind in quite a harsh manner.

What’s That All About?!

While presenting to the audience his Symphonic Poem in Two Parts, Mahler probably pinned big hopes on it. He had been composing his first symphonic piece with great inspiration; it mattered a lot to him.

Alas, the listeners poorly received the work. They considered it outrageous.

Gustav Mahler added a program – an explanatory storyline – to the piece. He named the composition Titan, a Tone Poem in Symphonic Form. This didn’t help.

Mahler dropped the program, excluded the title, and made some more revisions. The poem became Symphony No. 1…

Despite everything, the public mostly disliked his creation.

The decisive reason why the audience didn’t appreciate Mahler’s work was the fragment which today we know as the 3rd movement.

The music that opened it clearly imitated the heavy steps of a funeral procession, yet as soon as the respectable public imagined the mournful picture and tuned in to thinking about death, the procession started dancing. At a certain point, the dance became completely indecent – it already appeared a kind of buffoonery. People felt confused: what’s that all about?!

The most attentive listeners were especially bewildered. They discovered that the strange funeral march was based on the children’s folk song Bruder Jakob (or, in another version, Bruder Martin). Here is the song translated into English:

Brother Jakob, Brother Jakob, Are you still sleeping? Are you still sleeping? Don't you hear the bell? Don't you hear the bell? Ding, dang, dong, Ding, dang, dong!

Gustav Mahler didn’t want to tease anybody or mock the tragedy of human death. The combination of incongruous elements that he used carried a semantic load logically fitting into the general concept of his piece.

The Whole Distress of the World

Mahler’s symphony is a story of a youth, who grows up, encounters the difficulties of real life, and in a painful struggle finds his inner harmony (the title Titan, which symphony had for a short time, was the name of a young idealistic protagonist from a popular novel by Jean Paul).

The 3rd movement is the musical representation of the moment when he faces reality. That’s how the composer himself described this in a conversation with his friend*:

A funeral procession passes by our hero, and the misery, the whole distress of the world, with its cutting contrasts and horrible irony, grasps him. The funeral march of “Brother Martin” one has to imagine as being played in a dull manner by a band of very bad musicians, as they usually follow such funeral processions.

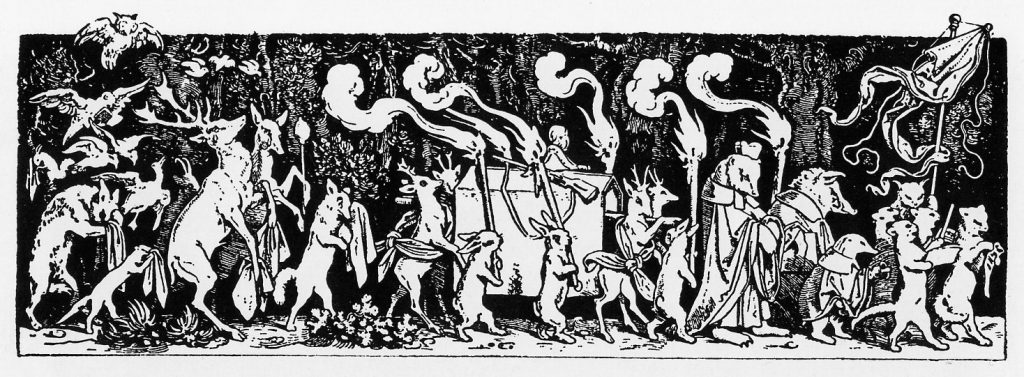

To better understand the mood of the music, look at the woodcut below:

The woodcut by Moritz von Schwind was the inspiration for the 3rd movement of Mahler’s Symphony No. 1. It illustrated an old Austrian folk story. Its characters – forest animals – led a funeral procession in honor of a fallen hunter. Hares and foxes, deers and boars pretend that they’re deeply saddened since it isn’t customary to have fun at funerals. They can’t hide their malicious joy, though.

What the hunter did was disgusting; the animal’s hypocrisy also seems loathsome. The dangerous enemy died. The forest dwellers needn’t be afraid of him any longer. These cowards shed their false tears just in case.

Gustav Mahler’s funeral march is a parody, but an incredibly sad one.

The composer subsequently often used the same device. Being included in emphatically serious works, lumbering funeral music, pretentious marches and frivolous waltzes sounded creepy.

Mahler’s compositions have a shocking effect even now, in the 21st century. They shock us to reach our hearts.

- “Секреты великих композиторов” – Артем Варгафтик, АСТ, Москва, 2021

- The Mahler Symphonies: An Owner’s Manual – David Hurwitz, Amadeus Press, 2004

*From Mahler’s conversation with his friend Natalie Bauer-Lechner

Thank you

I have very much enjoy the pieces you

Put together. You have raised my spirits

Thank you

Oh, I see. Mahler inspires in spite of the fact that his music can be incredibly tragic.

In English-speaking areas, we know Bruder Jakob in French by it’s French version – Frère Jacques – though we sometimes also learn an English version:

Are you sleeping, are you sleeping,

Brother John, Brother John,

Ring the bell for morning, ring the bell for morning,

Ding, dang, dong; ding, dang, dong.

Thank you for the interesting information!

Keep up the good work.

Thank you! I have a lot of ideas for my new articles, but – alas! – cannot write right now because of my broken right arm)